The Oku Ibom Ibibio, His Eminence, Nteyin Solomon Etuk.

Uwem Akpan, PhD – Uyo

“The greatest weakness of Nigeria’s cultural nationalists was that they emphasised only the negative results of missionary enterprise on the Nigerian society. But the Christian missions were more than destroyers; they were builders as well and, to some extent, preservers. Upon the Christian missions evolved the task of preserving the vernacular against the wishes of their converts and the indifference of the administrators who preferred the English language” (Emmanuel Ayandele, The Missionary Impact on Modern Nigeria. 1842-1914).

On Thursday, the 27th of August 2020, a significant milestone was recorded in the annals of Ibibio history as a result of the public presentation of the Ibibio Bible. This feat is a product of the missionary enterprise which began in Calabar on the 10th of April 1846, following the arrival of Rev. Hope Masterton Waddell, the purveyor of the Christian faith in Eastern Nigeria and his team, under the auspices of the United Free Church of Scotland (Presbyterian Mission). It should also be added that the Ibibio Bible is a manifestation of the proclamation of Rev. Waddell.

Towards the end of May 1858, Rev. Waddell had to retire finally from the service of the Calabar Mission. Greatly satisfied by his pioneering role, the people of Creek Town sent through Rev. Waddell the sum of £71,000 (a huge amount of money then) as thanks offering to the Mission treasury. Farewell sentiments were expressed by the people for the departing hero of the faith and his dear wife. In his final words, Rev. Waddell proclaimed thus: “we left Calabar with confidence. The past caused no regrets and the future no apprehensions”. He also prayed that God’s work which he began in the Old Calabar area should continue forever.

It is not the intention of this writer to undertake holistic contributions of the missionaries in the Old Calabar area. Attention will only be focused on the genesis of the translation of the Bible in vernacular – Efik language. Moreover, since the writer intends to pay a tribute to the “father of vernacular Bible in Nigeria” – Rev. Hugh Goldie, as part of the celebration of the publication of the Ibibio Bible, his name and contributions will only be mentioned in passing here. It is on record that Rev. Goldie pioneered the translation of the New Testament into Efik in 1862. Due to the painstaking effort of Rev. Goldie, in conjunction with Alexander Robb, the complete Efik Bible came out in 1868. By this development, the Efik Bible was probably one of the first Bibles to be translated into an indigenous language in West Africa.

READ : Police parade four suspects in connection to murder of two persons in Port Harcourt

The questions that need to be answered are, why was the Bible translated in Efik and not Ibibio language? How come that the Ibibio, Nigeria’s fourth largest ethnic nationality had to speak Efik as its official language and also read the Efik Bible? To answer these questions, there is need to resort briefly to history.

Even though in recent times the Efik have denied being of Ibibio origin, they do not argue that their ancestors had lived in Uruan clan of Ibibio nation for many generations. Some Efik sources estimate the period to have been between 160 to 200 years. The name Efik is from the Ibibio verb, fik (to oppress, to press down with a weight). Following the movement from Uruan, the Efik ancestors migrated across the Cross River to an Island known Ikpa Ene and afterwards moved to Obio Oko known as Creek Town, so named because of its location at the bank of the Cross River Creek.

Over time, apart from Creek Town, other Efik settlements developed. They included: Old Town (Obotong), Duke Town (Atakpa), and Henshaw Town (Nsidung). It should be added that by the time the Efik arrived the present-day Calabar, the Efut and Qua (a section of the Ejagham) had already settled there.

Due to their geographical location at the estuary of the Cross River, which empties into the Bight of Biafra and also receives numerous streams to its right and left banks, the Efik exercised control of the entrance into the Atlantic Ocean. Consequently, the Cross River had a tremendous impact on the economic and social life of the Efik and largely dictated the direction of Efik expansionism and influence. Erudite Ibibio Professor of History of blessed memory, Monday Noah posits that “the Efik exploited the opportunities afforded by their location to achieve extensive economic power. Economic power carried considerable political and cultural significance”.

Advertisement.

Advertisement.

Based on their strategic location at the entrance of the Atlantic Ocean, the Efik became one of the earliest peoples along the Nigerian coast who came in contact with the Europeans. For instance, available records show that the Portuguese had arrived the area in 1472. Through this early contact, the Efik were able to learn European manners and customs and also seized the opportunity and sent their sons abroad to acquire Western education even before the advent of the Presbyterian missionaries in 1846, a development that ushered in the establishment of the first formal school –Duke Town School, established by Samuel Edgerley who was in the pioneering team. Following the introduction of Western education in Calabar, other schools were established and Efik people embraced the system. The outcome of this development was that Efik language became the language of commerce and civilisation. It was widely spoken in the Cross River region including the Southern Cameroon. The scenario caused the Efik language to “swallow” the Ibibio language – its Proto language.

Based on linguistic and ethnographic studies of the Ibibio and Efik, Nair, submits that “there are some linguistic proof that Efik is a dialect of the Ibibio language, and that it separated from the other only within the last centuries”. Simmons also notes that a comparison of 195 Ibibio and Efik words on the Swadesh basic vocabulary list revealed 189 cognates (95 per cent). He adds that this high percentage of the cognates indicates recent separation of the two groups.

Edet Akpan Udo in his seminal work, Who are the Ibibio? notes that Christianity and commerce constituted the two main factors that facilitated the transformation of Efik as the lingua franca within the Cross River region. He points out that first “the members of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland who began their evangelical education…established schools and churches among the Efik; second, the missionaries translated the Efik dialect into writing; third, they produced Efik vernacular readers for use in Efik schools; they also translated the English Bible and the English hymn book into Efik and published a dictionary in Efik”.

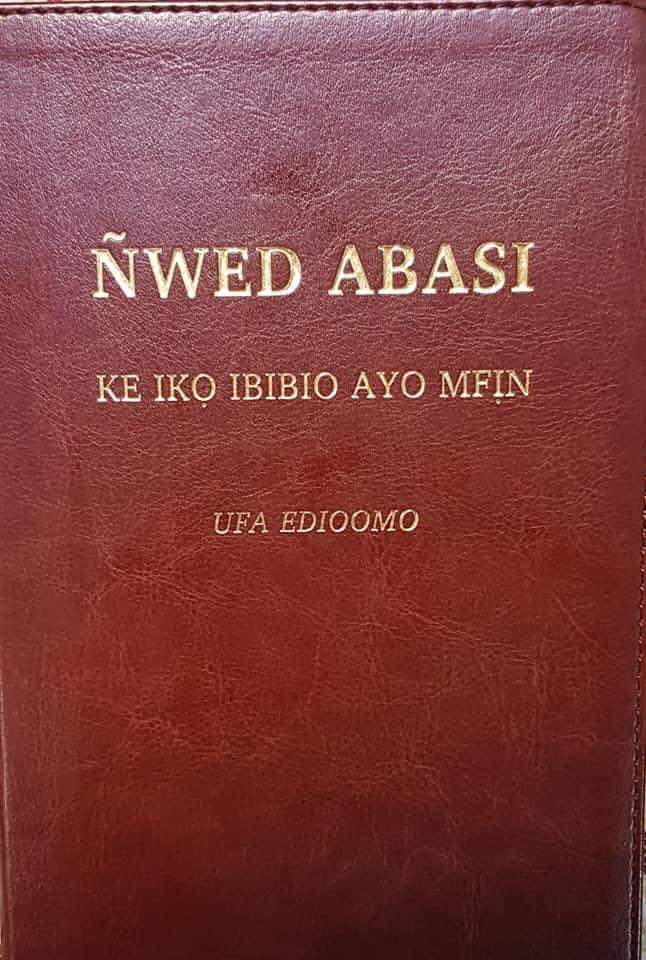

The back cover of the newly translated Ibibio Bible.

The back cover of the newly translated Ibibio Bible.

He also avers that “As with trade in slaves and in politics, the Efik also controlled Western education and prohibited its spread into Ibibio land. They did this for about 60 years (1846-1906). Therefore, when in 1846 the United Free Church of Scotland arrived Calabar and began their evangelical, educational and social services, they were asked to restrict their work to the Efik. This was because the Efik found Western education to be a new source of power and wealth, a source of power which was greater than that offered them by their Ekpe society”.

Udo observes further that “in consequence, the United Free Church of Scotland established a school in 1858 at Ikot Offiong, an Efik trading station in Ibibio land. Two years later, Archibong II of Duke Town banned missionaries from going up the Cross River beyond Ikot Offiong. Although Uruan clan borders Western Efik land, the Church of Scotland Mission was not allowed to open their schools and churches there until after the opening up of the Ibibio country in 1902 by the British Government. It was during the scramble for the mission spheres of influence (1904-1952) that the United Free Church of Scotland was permitted by the Efik to penetrate the Ibibio country…”.

It should also be mentioned that the flowering of Efik language occurred to the detriment of the Ibibio language. Colonial records reveal that attempts to write and develop the Ibibio language happened at the time the Efik was about to be written (between 1846 and 1862), when Rev. Goldie’s Dictionary of the Efik Language was published.

According of M.D.W. Jeffreys, a popular colonial anthropologist and administrative officer in Southern Nigeria, the first attempt to write Ibibio was defeated by two votes. He explained that “at the language conference held in Calabar, the motion to impose the Efik dialect on the Ibibio race was carried by two votes…only because two members refrained from voting”.

In spite of the initial set-back for the Ibibio language, Jeffreys, produced orthography for the Ibibio language and made a passionate plea to the missionaries and other authorities that Ibibio be used officially, side by side with Efik for mutual benefits. But this orthography was rejected and an attempt to make Ibibio an official language failed.

In his reaction to the situation, Rev. Smith in a quarterly “Africa, Vol. II, No. 4”, writes that “it is recommended that Efik, the dialect of about 30,000 persons of mixed descent, be forced on 650,000 pure Ibibio. The reaction was based on his postulation entitled “a shrine of the people’s soul”. According to him, “every language is a temple in which the soul of the people who speak it is enshrined”.

The missionaries’ conspiracy which was the rejection of the Ibibio language made the language to remain unwritten and also be un-official for decades until 1983, when with the sponsorship of an Ibibio cultural organisation, Akwa Esop Imaisong Ibibio, an orthography was produced and presented to the Ministry of Education of the then Cross River State. In this respect, tribute must be paid to some Ibibio elites such as Professors Okon, Essien, Elerius Edet John, Ime Ikiddeh, Monday Abasiattai, Monday Efiong Noah and Mr. Sonny Samson-Akpan. These geniuses also formed the Ibibio Language Writers Association (ILWA), a body that enhanced some path-breaking books in Ibibio language.

This scholarly energy generated in the 1980s particularly after the creation of Akwa Ibom State in 1987, gradually snowballed in the Ibibio Bible. Information in the public domain shows that the Ibibio Bible was initiated by Professor Okon Essien. The translators include Professors Margaret Mary Okon, Bassey Okon, Eno-Abasi Urua, Inimbom Akpan and Udo Etuk. Others include Drs. Paulinus Noah, Effiong Ekpenyong and Rev. Fr. Dr. Donatus Udoette. The Ibibio Bible is published by the American based International Bible Society, publishers of the New International version of the Bible (NIV).

The bitter truth that needs to be pointed out is that just like the Efik elites and early Christian missionaries despised and rejected the Ibibio language, the Ibibio of the present generation still despise the use of their language.

At present, the interest in the use of the Ibibio language has extensively diminished. The Ibibio prefer foreign and “Bible” names for themselves and children. Children are instructed in English language at home and in school. Events such as church services, traditional marriages, burials in typical Ibibio communities are conducted in English language. In the Ibibio churches, the acceptable songs are not in Ibibio language, but in English, Efik, Igbo and Yoruba. Also, preaching is done in English language to easily “activate the anointing”.

READ ALSO Ondo state inaugurates 14 member public procurement board

In fact, one of the most frightening actions of the present administration in Akwa Ibom is the stoppage of news translation in Ibibio language in both Akwa Ibom Radio and Television stations. This action is a clear indication that the Ibibio people do not have the need for their language.

For the Ibibio language not to “die” like the Efut and Kiong languages spoken by the Efut and Okoyong peoples of Cross River State, there is an urgent need for the introduction of Ibibio language as a compulsory subject in primary and secondary schools in Akwa Ibom State. Ibibio should also be introduced as a course in Akwa Ibom State University while the Department of Efik/Ibibio in the University of Uyo should be supported by the Akwa Ibom State Government. In fact, students offering this course should be made to enjoy some special incentives and tuition free studies. Teachers of Ibibio language should also be trained and re-trained regularly. Moreover, the Akwa Ibom State Government should immediately order the restoration of the translation of news in Ibibio language in Akwa Ibom Television and Radio stations.

If these measures and related ones are not taken immediately, the Ibibio Bible would have been a wasted venture, because there will be no readers of the Bible. Moreover, the stakeholders in Ibibio land should also join in the process of re-orientation to reclaim the lost heritage.

While we commend those that directly and indirectly facilitated this legacy, a call is hereby made to all stake holders in the Ibibio project to put in place a strong and vibrant team to translate the Old Testament of the Bible in Ibibio. As mentioned above, the team led by Rev. Goldie completed the translation of the Bible in 1868 after the New Testament had made its debut in1862, a period of six years. When this has been successfully done, the mission would be fully accomplished. However, it is indeed of historical significance that the Ibibio people now have a Bible in their own Ibibio language after 158 years.